If you know me in person, you know I love Halloween, but I also love the spooky, the macabe, and the mysterious. In the lead up to Halloween, I’ve been thinking a lot about the spooky stuff of art history. Death, witches, ghosts, and the occult are only the beginning to some of the insanity seen throughout art history. This may become a series, not simply for Halloween, so keep an eye out for more Spooky Art History!

The Renaissance period is often considered such an important moment in art history because of the advancement in realism through better understandings of perspective, but also anatomy. But how did artists during this period (and for many many years after) learn about anatomy and biology?

Corpses.

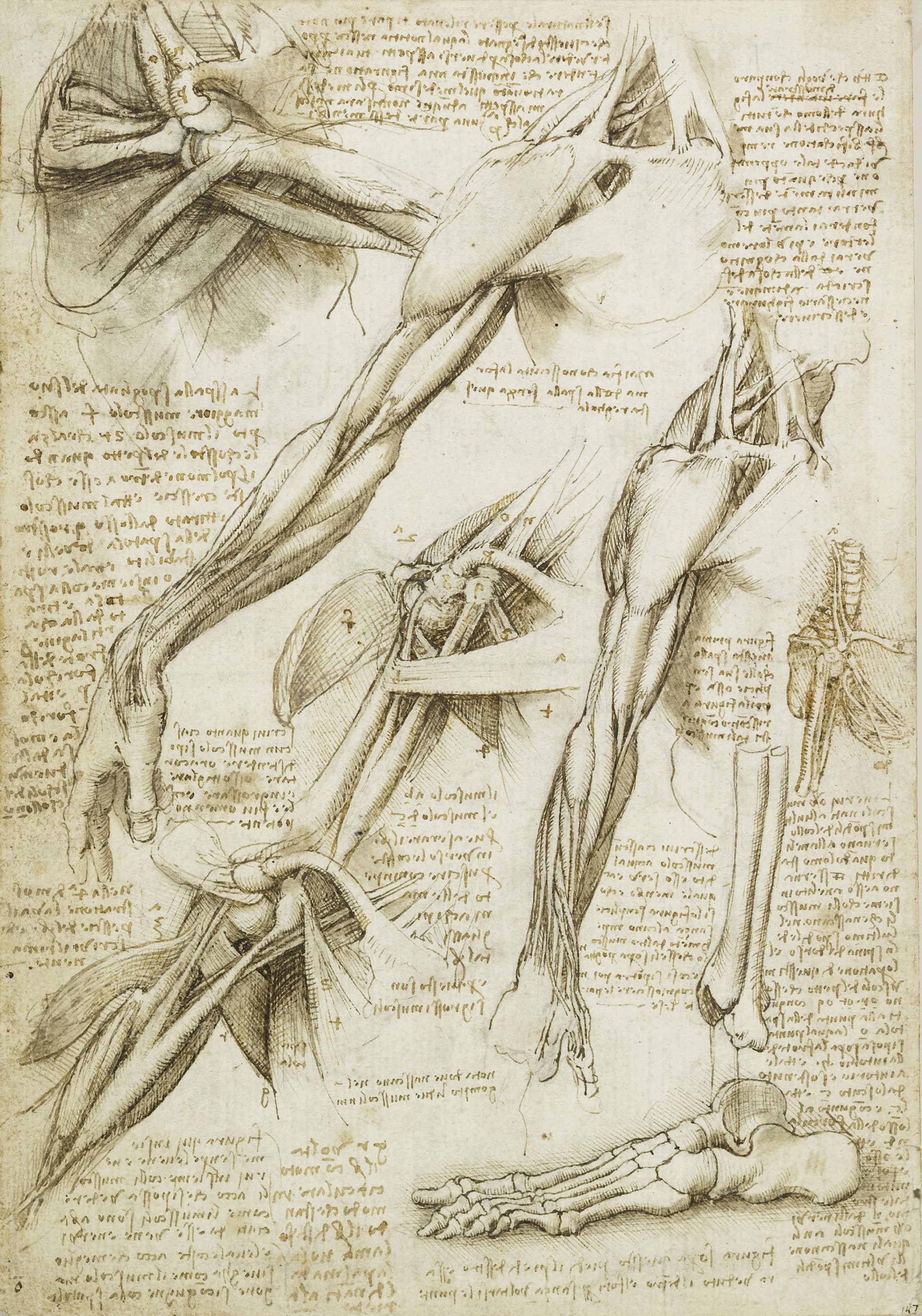

For artists such as Leonardo, the best way to understand how the human body was shaped and how it moved was by getting inside. Leonardo dissected over thirty corpses, an act that was in defiance of the Catholic church. Dissection was considered illegal unless you were a physician. Due to the illegal nature of dissection, artists often worked with grave diggers who would bring them recently buried bodies to work with. Eventually, Leonardo was given special permission to continue his studies of the human body with the assistance of a hospital director and Leonardo’s studies offered some major discoveries and new understandings of the human body. His notebooks are filled with drawings, such as the one above, of muscles, bones, and organs that had previously been misunderstood or unknown to physicians and scholars before him.

One way later artists showed their knowledge of anatomy and artist still was through works called “écorchés,” studies of the body that peeled back layers to reveal muscles and the skeletal system, such as this study by sculptor Domenico del Barbiere.

With artists like Leonardo and Michelangelo seen as the peak of artistic skill, the idea of who an artist was expanded beyond just a craftsman who could create beautiful images but into a true academic and learned person. Extensive study and learning of science, mathematics, and more was another sign of excellence and skill.

The interest in studying the body continued for centuries as medicine advanced and understanding of the human body grew. When artists wanted to capture reality, they often turned to studying the human body to ensure they depicted the body as accurately as possible.

This trend was again popular during the French Romantic period with artists such Theodore Gericault. If you follow our Instagram, you may have seen one of Gericault’s works, “The Raft of the Medusa,” featured on the page. This large scale painting was a spectacle because of Gericault’s dedication to accuracy and realism. Gericault met with survivors of the shipwreck who survived thirteen days at sea, built a model of the makeshift raft the survivors were on to understand it’s shape and movement, but most of all, Gericault wanted to depict the bodies of the many who did not survive the long days at sea. He studied corpses, looking at the way the skin discolored with time, how their bodies may have been bent in strange ways, to capture the reality of the fifteen survivors who were rescued, surviving by resorting to cannibalism and existing day after day surrounded by the dead.

Gericault depicted the dead and those dubbed “insane,” wanting to capture the emotion of life and death while living during a period of great unrest and uprising in France. In 1818, Gericault painted the head of a recently guillotined man. The head is slightly propped up, surrounded by a dark background, and Gericault captured the green-ish color of the dead man’s skin and the sharp angles of the man’s gaunt face. The painting, now displayed at the Art Institute of Chicago, is both shocking and serene. The peaceful face of the dead man is juxtaposed by the gore and dark red of the violent decapitation.

There is something to be said about the way artists utilized the dead to better understand the living. Studying their bodies allowed Renaissance artists to develop new techniques and more attention to detail in the shape and movement of the human body. Men like Leonardo advanced the medical field significantly by drawing diagrams and studying anatomy, allowing people to better understand and care for their bodies. For artists like Gericault, they studied and worked with the dead to understand death during a time of uprising, executions, and revolution. His depictions of executed men or people lost in a scandalous shipwreck confronted the viewer with the good, the bad, and the ugly about death and often provided a strong narrative about the implicit role the tumultuous government had in the deaths of these people.

I began thinking a lot more about the lessons learned from the dead following a video from mortician Caitlin Doughty on her Youtube Channel, ‘Ask a Mortician,’ and I know there is so much more to discover about the relationship between art and death.

What are some other examples of how artists throughout history have turned to the dead for knowledge, insights, or inspiration?

-Claire Sandberg